Congenital Heart Defects in Individuals with Down Syndrome

February is Heart Month, a time to bring awareness to heart conditions. Congenital Heart Defects affect approximately 50% of babies born with Down syndrome, (compared to 1% of neurotypical children).

Throughout the decades, there has been dramatic improvement in the quality of care: surgeons are able to repair heart defects, and other specialists such as “interventional cardiologists” who have specialized skills in performing specific types of surgeries that were not available long ago, came into existence.

How does the heart work?

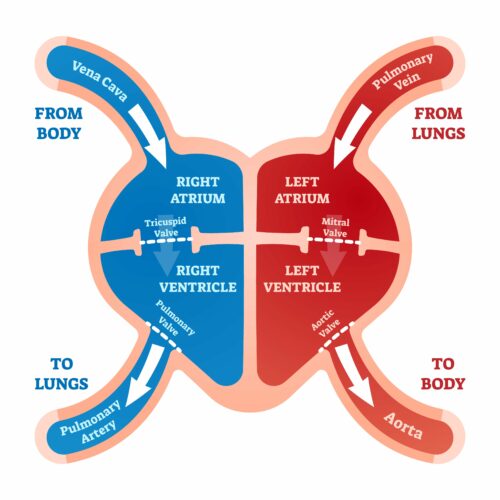

To understand congenital heart defects, it’s important to understand basic cardiac structure and function:

If you hold your hand in a fist, your fist is about the size of your heart. Your heart is both electrical and mechanical.

The purpose of the heart is: on the right side to pump blood to the lungs to oxygenate them. Then the lungs oxygenate that blood and return it to the left side of the heart through the aorta, which is a big blood vessel at the top that provides your body’s systems, organs, and brain with an oxygenated blood supply.

The heart is divided into chambers. The upper chambers are called the Atria and the lower are called Ventricles. The left ventricle is much larger than the right because it’s the workhorse of the heart and it needs to pump out all that oxygenated blood to the rest of the body. Within the heart there are also chambers and four valves.

The heart itself is a muscle, and it must receive its own supply of blood too, which it receives from the coronary arteries. When we hear about heart attacks, this is what it’s referring to, one of those arteries or a branch of those arteries has been blocked.

Besides those mechanics of the blood supply, the heart is also electrical. What causes the heart to pump, is the electrical conduction system that starts on the right side of the heart. There’s an area called the SA node, which is considered the pacemaker of the heart. That stimulus goes throughout different fibers into and around the heart to help it pump. With congenital heart defects there are some potential conduction problems even after repairs.

Heart development:

The heart develops at about five weeks in embryo. It starts as two tubes that merge to form the heart, then they develop into cushions. The heart starts to beat and pump around day 21 of gestation.

With Down syndrome, the cause of congenital heart defects isn’t clear, however the addition of genetic material could likely alter the course of development in utero, which could affect the development of the heart. Some other effects are narrow upper respiratory tract, smaller trachea, hypotonia (connective tissue disorder).

Other causes of congenital heart defects:

- Maternal alcohol consumption or drug abuse

- Maternal antiepileptic medications

- Genetic conditions (Turner syndrome; Noonan syndrome, PKU)

- Viral infection (flu, rubella in First trimester)

- Medications (Lithium; isotretinoin)

- Maternal diabetes types I and II, (not gestational)

- Organic solvent exposure

Most common congenital heart defects in Down syndrome:

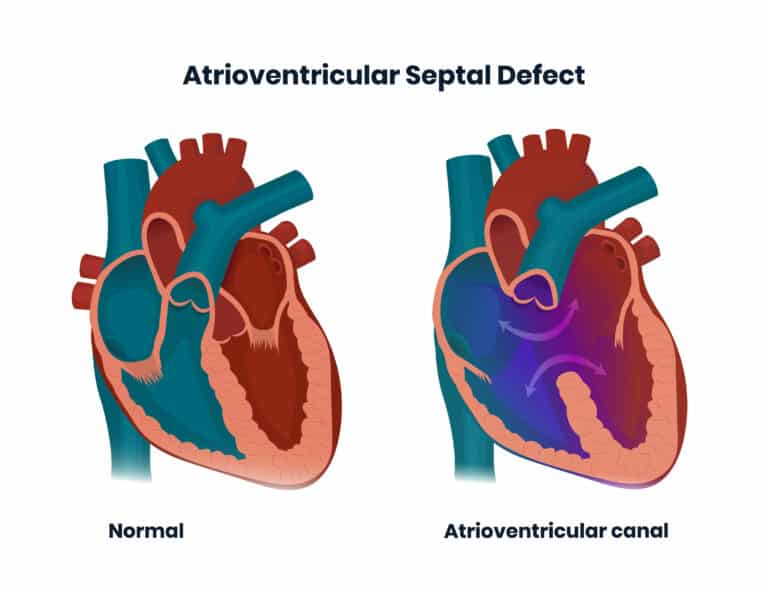

Endocardial Cushion Defect / Atrioventricular Septal Defect:

This consists of a hole between the upper chambers in the heart (atria) where the blood flows. It can cause a left to right “shunt.” In other words, it can make the blood flow deviate from its normal circuit.

Babies born with this condition can be prone to respiratory infections and poor weight gain. Adults with untreated conditions can develop atrial arrhythmias, (upper chambers of the heart) which although not life threatening, can cause problems since the upper chambers quiver, and while they are not getting a good blood supply to the ventricles, they can set off blood clots that can either go to the lungs, (pulmonary embolism) or to the brain and cause a stroke.

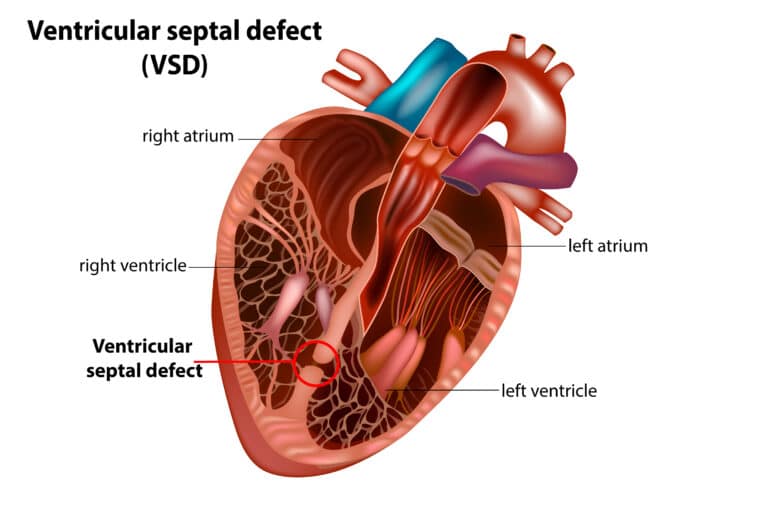

Ventricular Septal Defect:

This is a hole between the ventricles, (lower chamber in the heart) which causes the blood to flow back and forth. This causes high pressure in the ventricles and for unoxygenated blood to flow from one ventricle to the other, increasing the blood volume in the lungs. The right ventricle, which in normal conditions pumps blood to the lungs to oxygenate it, will create congestion in the lungs.

Typically, this hole closes before birth, but an open hole goes on to cause problems such as: making the lungs work harder, reduced oxygen to the body, the person affected will have difficulty eating, slower growth, and it can also cause damage lungs and blood vessels.

This defect also causes high pressure, resulting in loud murmurs that are not life threatening .

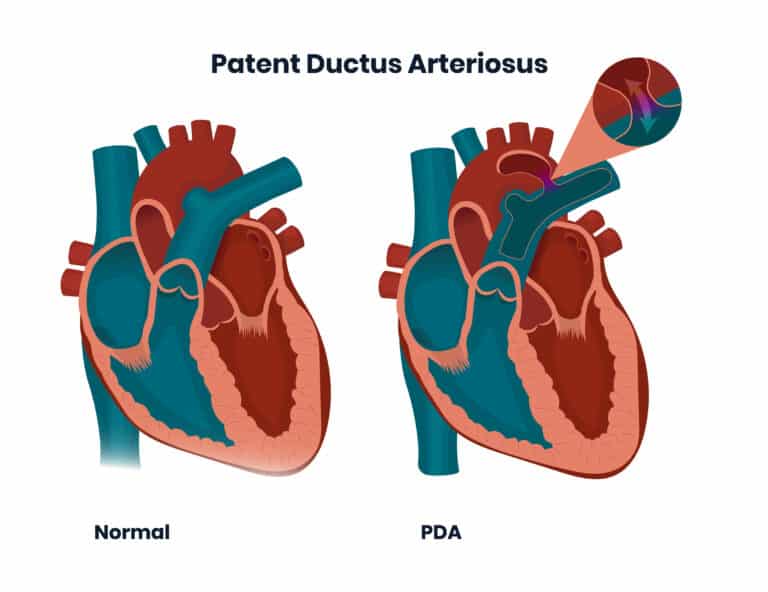

Patent Ductus Arteriosus:

This is a channel between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. The reason why it exists is to divert blood from the lungs in utero, because the baby is already getting oxygenated blood from their mother.

Most times this hole closes with growth. In neurotypical and full-term babies, it usually closes within the first day of life. But the automatic closing is often delayed with a premature or neuroatypical child.

Depending on the circumstances, doctors may recommend medication or surgery.

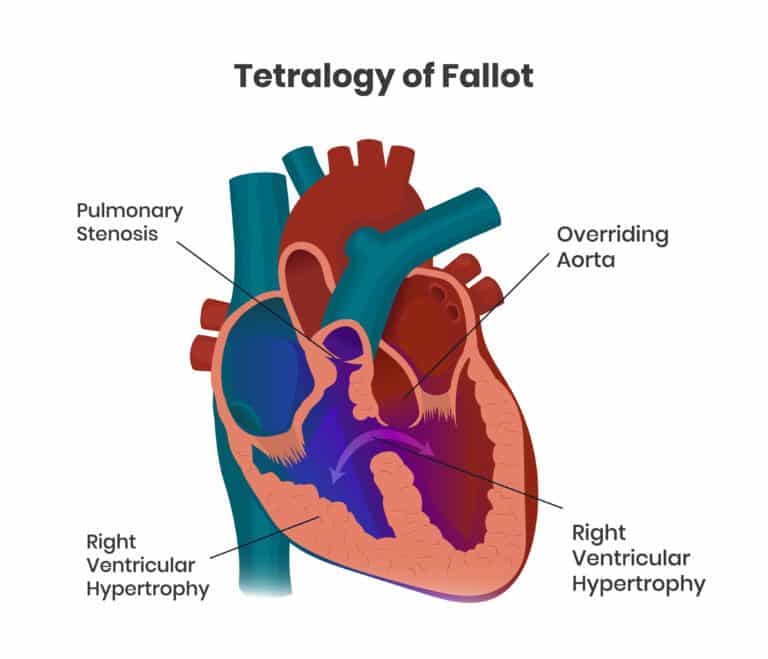

Tetralogy of Fallot:

This is a rare condition consisting of a combination four heart defects present at birth: ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy and overriding aorta. This will change the way the blood flows to the lungs and through the heart. In most cases, too little blood flows to the lungs. The blood that flows carries too little oxygen, therefore, too little oxygen reaches the tissues.

A recognizable symptom in babies is that they will have a blue tint of the skin, nails, and lips.

If left untreated, the child may develop cyanosis that gets worse (blue tint), dizziness, fainting and seizures and higher risk of endocarditis.

The recommended treatment is open heart surgery, which is performed soon after birth or later in infancy depending on the child’s health and weight.

Treatments for congenital heart defects:

Treatment will depend on the type of congenital heart defect. In some cases, for instance in the case of Ventricular Septal Defect, if the hole is small enough, sometimes the condition can be managed with medications and monitoring. In other cases, surgery might be prescribed.

For children who need surgery, doctors recommend it is performed within the first year of life. Early surgery is important to decrease any lung damage. However, depending on the severity of the condition, more than one surgery may be required.

But even with these significant leaps in medical advances, experts recommend regular monitoring. Successful repair of a congenital problem is not a full cure in most congenital heart defect patients, and they do require ongoing monitoring and treatment to help navigate the risks of living with cardiovascular problems throughout their lifespan.